by Nii

Ayikwei Parkes

|

| Supermarket Bananas with Spider |

In the

last fifteen years, I have found two trends in Western news

particularly fascinating; one is quirky and the other is odd. The

first is the increasingly frequent articles showcasing some stunned

family that has found a 'dangerous' tropical critter in their bananas

or in the fruit aisle of their local supermarket and the second is

the almost-as-regular opinion pieces on how governments ignore the

voice of the majority. I think these trends fascinate me because in

Ghana specifically and, perhaps, in the so-called developing world as

a whole, these things are not news, just pesky thin-limbed things we

would brush off our shoulders. However, with reflection, I am

probably also drawn to these curiosities because they are metaphors

for how the bad can lurk in the ostensibly good.

I think of

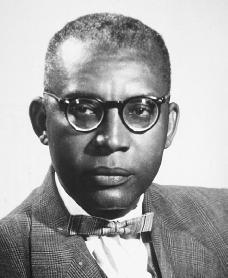

these things today as a reflect on the 108th birthday of

Ghana's first president, Osagyefo Dr Kwame Nkrumah and how, as a

child, I would rarely hear good things about him outside of my own

home, where my father had a near-complete library of Nkrumah's

writings. My late father – firm friends with the daughter of J.B

Danquah, a man famed as one of the most prominent victims of

Nkrumah's Preventive Detention Act of 1958; and married to a niece of

General Ankrah, the man who overthrew Nkrumah – was no apologist

for Nkrumah's excesses, but was appreciative of his vision and the

real positive changes that he had seeded in Ghana. He considered the

man a flawed genius. It is in this ambivalent space that I came to

know Nkrumah – all my history books painting him as a wasteful

despot who had left Ghana in debt; my father insisting that we were

the best-educated nation in Africa, even with a large number of

skilled Ghanaians stranded in exile after the coup d'état of 1966

that ended Nkrumah's reign.

|

| Doc Duvalier |

With my

own study of the history of the Enlightenment and Capitalism as a

whole, as well as my almost natural interest in coups d'état given

that I experienced my first when I was five years old, I have come to form a number of new opinions on Nkrumah, his successes and failings. There are two primary ones;one is that regardless of the

economic system he was believed to have leaned towards, Socialism or

Capitalism, they are both Western systems based on the notion of

acquisition as development, and inherent within the quest to keep up

with the Smiths and Joneses is a seed of despotism, which he could

not escape; two is that his real crime, which rid him of the

Western support that despots such as Pinochet of Chile, Mubarak of

Egypt, Duvalier of Haiti, Mobutu of Congo, Jiménez of Venezuela,

Marcos of the Philippines, Habre of Chad and Tito of Yugoslavia

enjoyed, was that within his mission was a leaning towards

self-sufficiency that would effectively impoverish the supply line of

dependence pivotal to the West's economic and political leadership of

the world as we know it. The first was his curse, the second was his gift (to us, not the West). To my mind, the second notion is what

aligns Nkrumah with Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso and Patrice

Lumumba of Congo.

Perhaps

the greatest trick of Western-style development peddlers is the

neglect to qualify that the engine of such development is

subjugation. It's just like your organic fruit seller forgetting to

tell you that not using pesticides means that you are more likely to

get a friendly spider or scorpion from Panama in your bunch of

bananas. They won't tell you that because then they can't charge you

the premium you pay to eat organic fruit. Their aim is to sell fruit

just as development peddlers aim to sell Western-style development.

The Swiss-born philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau had plenty to say

about the ills of the materialism and individualism that lies at the

heart of this model of development, lamenting in his Discourses

that it makes “all men competitors, rivals or rather enemies”

resulting in “a multitude of bad things for a small number of

good”.

Much of

the wealth that became the engine for Europe's development was earned

under Feudalism, with majority of the population barely paid for

their labour, this was followed by largely autocratic regimes and,

for the most economically successful, the Transatlantic Slave Trade

and colonialism. In fact, it is stunning how soon after the

beginnings of the decline of Feudalism (early 16th

Century) the Slave Trade starts to flourish and how the legal

abolition of Feudalism in England, for example (The Tenures Abolition

Act 1660), coincides with the time when the English become the

leading shippers of slaves from West Africa. With these immeasurable

advantages in place, England exploded in wealth and edifices.

Immanuel Kant, the German philosopher, celebrates in several writings

the motivating power of competitiveness and vanity and, sure enough,

the rest of the world has sought to display its own edifices and

wealth since. Russia, in seeking to catch up with the English and

French, were under the tyrannical rule of first Peter the Great, then

his successors until Catherine the Great; the United States of

America had chattel slavery. So, yes, governments ignore the voice of

the majority when they seek material gain. (Anyone remember the Iraq War?) The Enlightenment and

colonial era exploitations I mention are near impossible to duplicate

and the closest a nation can get to those conditions is some form of

despotism. Of course, this only counts if your notion of development

is the Western model – and Nkrumah, with his Western education,

could not help but be shaped by these ideas and therein lay his seed

of dictatorship. People had to be dominated.

There is a

quote from Rousseau on kings, which I believe speaks to both

Nkrumah's gradual slide into despotism and the graveness of what I

have called his real crime, which, of course, is no crime at all!

“...political sermonisers may tell [kings] to their hearts'

content that, the people's strength being their own, their first

interest is that the people should be prosperous, numerous and

formidable; they are well aware that this is untrue. Their first

personal interest is that the people should be weak, wretched, and

unable to resist them.” For Nkrumah, his primary desire was

that the people should be unable to resist him, to see him as

Osagyefo – the redeemer – and trust them to lead them into a

golden era. This makes him no different from all the men – yes, men

– I have listed above who put their people through hellish times

far more extreme than Nkrumah ever inflicted on Ghanaians. So, why is

he one of the leaders (like Lumumba and Sankara) that the Western

powers sought to eliminate? The answer is simple – commerce.

Nkrumah's plans were increasingly headed in the

|

| Silos in Tema (image source njnrr) |

Given

these facts, it is no wonder that for years care has been taken to

inform us that Nkrumah left Ghana in debt, but little light is shed

on why the men who deposed him were encouraged to let every factory

and silo that was in development waste away. The sad thing is that,

the military goons (my great uncle included) in their sycophantic

ardour didn't realise that if the factories didn't work, the money

for the loan repayments would have to come from somewhere else.

That's the other thing with the banana sellers; they don't tell you that if there is an infestation of African cockroaches you have to deal

with them yourself. They can instigate coups d'état, but they don't

erase national debt.

Ultimately,

as Pankaj Mishra says in his recent The Age of Anger, “whether

or not the non-West catches up with the West, the irrepressibly

glamorous god of materialism has superseded the religions and

cultures of the past in the life and thought of most non-Western

peoples”; in many ways, the Nkrumah ship has sailed for Ghana, but

our journey as a nation continues. Conditions as they existed during

his reign will never return, but we can still learn from his

philosophy of finding our own approaches to development, the innate

instinct that made him deviate from a pure Western, global approach

and look inside first. In the meantime, let's remember our

self-sufficiency despot with a little more balance.

what i'm reading/listening to

listening:

Gene Ammons - Stranger in Town

reading:

Age of Anger

No comments:

Post a Comment